Climate change risk

The risk landscape

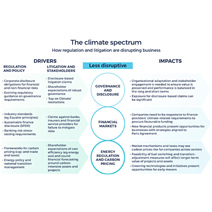

Corporate approaches to climate change issues are under increasing scrutiny around the world. Climate change litigation, legislation and policy are increasingly used as tools to influence corporate behaviour, although trends differ markedly by jurisdiction.

Location, location, location

The legal risks and challenges associated with climate change are distinctly jurisdiction dependent.

For example, in the US, claimant-friendly procedural rules and long-standing judicial experience of mass claims have established the country as an epicentre of climate change-related litigation. By contrast to the very litigation-heavy approach in the US (and certain other jurisdictions, including Australia), the EU and the UK have seen developments towards more robust and consistent regulation as a means of driving behavioural change.

We expect these jurisdictions will continue to exert significant influence on the development of regulatory frameworks elsewhere. In China, broad policy and legal initiatives that mandate deep and sweeping changes across sectors of the economy can result in very rapid economic change, but have not so far given rise to many cases in Chinese national courts or disputes with public authorities.

The locations in which a business operates, and its activities there, are therefore integral to the picture of the climate change-related legal risks and developments that it will have to grapple with. Public company listings in the world’s major financial centres, and the impact of changing expectations from finance providers based on the increased regulatory and political scrutiny they are facing, will also play an important part.

Stakeholder pressure

Stakeholder scrutiny of climate change-related disclosures and policies continues to increase. From shareholder “Say on Climate”-type resolutions to NGO activism in the form of regulatory complaints and formal (often strategic) litigation, a range of stakeholders are utilising available tools to try to effect corporate change, challenge policies or projects that are considered inconsistent with the targets set out in the Paris Agreement, or seek compensation for past or anticipated future climate-related damage.

Regulatory disruption: risks and opportunity

Changes introduced by national governments and supranational organisations to address climate change can create significant disruption for companies as they seek to remain legally compliant and optimise their business performance. Some of these changes are likely to be manageable without changing business fundamentals, including by making changes to governance and reporting, assessments of existing practices, active stakeholder management and organisational adaptation. Other changes are intended to have inevitable and profound effects on the structure of business activities and/or sectors of the economy, and are likely to be impossible to appropriately mitigate through anything other than strategic business re-alignment.

Companies that are alert to the opportunities and risks presented by the changes these initiatives will drive will be better placed to protect and accrue value through these changes. A lack of management awareness of, or responsiveness to, the level of change that initiatives are seeking to drive should act as a red flag.

Download the full graphic here.

Governance and disclosure

Climate change issues are often embedded within a range of considerations that key decision makers need to have regard to as a matter of national corporate laws.

For example, directors may be required to ensure adequate planning and risk assessment regarding climate change have been factored into the company’s strategy. Fiduciary duties of investment managers, asset owners and pension fund trustees should also be considered in the context of increasing ESG concerns, including climate change.

Obligations to disclose climate change-related information are also generally contained within established disclosure regimes to help stakeholders make informed investment decisions.

Not all stakeholders and observers consider that it is appropriate to give significant weight to long-term risk mitigation and planning. Traditionally, these governance and disclosure laws have been intended to safeguard value for shareholders, who are often focused on shorter-term returns. Our landmark 2021 report for UNEP, A Legal Framework for Impact: Sustainability impact in investor decision-making, provides detailed guidance on this balancing process, drawing out the complexities of considerations for investment decision -makers in all key markets.

One area where longer-term considerations are likely to matter more is in the context of acquisitions, where long-term risk may impact the valuation of a target.

Practically, the weight accorded to climate change considerations will likely depend on the views of stakeholders and on the context of a company’s activities and performance. For management, understanding how climate change factors form a component in stakeholders’ assessment of the business’ value (and why) is likely to be an essential and potentially complex exercise.

Financial markets

The growth of financing initiatives that are directly concerned with climate change has been exponential in recent years, and remains a central concern of policy and legislative programmes, often developed to support energy transition strategies.

Investors and companies working towards sustainability goals and climate change-related targets are increasingly looking to sustainable financing instruments, including green bonds, loans and mortgages, and sustainability and climate bonds. Green bond issues alone are expected to exceed half a trillion dollars by the end of the year.

However, due to a lack of agreed benchmarks it can be hard to compare how green different products and providers are. Law makers and industry bodies are becoming increasingly involved in developing benchmarks to address the concerns of investors and other stakeholders, and frameworks such as the proposed EU taxonomy and the UK’s green taxonomy are being implemented to provide clearer guidance. The development of a global standard for sustainability and climate change- related criteria is not certain and would take time. The uncertainty of existing credentials can lead to ‘greenwashing’ accusations against businesses.

Providers of finance and financial services may also pass on climate change requirements to their customers as they become subject to greater scrutiny and the risk of claims for failure to mitigate climate change risks.

Energy regulation and carbon pricing

National policies increasingly prioritise increased deployment of low-carbon energy generation assets and incentivise energy efficiency. Government incentives generally interact closely with the landscape for direct foreign investment in the relevant jurisdiction and its suitability to specific energy generation assets.

However, government-supported transition measures are often made more complicated by challenges that may be brought by adversely affected parties against the public authorities which design, implement and supervise the relevant policy schemes.

Initiatives aimed at reducing emissions from carbon-intense sectors may include requirements for emission reduction planning, or impose additional costs on carbon-intensive activities. Other initiatives include incentivising larger consumers of energy to switch fuel sources, and addressing the economic problems associated with the energy transition for established businesses, in particular where there may be stranded assets or significant impacts on employment potential.

Cap-and-trade schemes and direct carbon taxation (collectively referred to as ‘carbon pricing’) are major elements of many of these regimes. The future of cap-and-trade schemes in particular may be at a turning point. The expected introduction of the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism in the EU, the rising price of EU Emissions Trading System allowance instruments and the roll out of Germany’s National Emissions Trading Scheme may indicate a more robust carbon pricing regime is on the horizon in Europe. And in China, a national carbon trading market was launched earlier this year, mainly covering emitters in the power sector.

Meanwhile, Australia remains resistant on carbon pricing as a policy option, while some US states are taking action amid US federal uncertainty and Canada is consulting on the possible creation of its own carbon border adjustment measure.

Planning and operational controls

Decisions regarding the use of land for industrial or energy-intensive activities are often taken by public authorities that are subject to legal duties to take into account certain considerations, including climate change. Planning decision makers are increasingly challenged to give weight to climate change considerations, and the implications for major projects can be very significant.

This will mean that assessing the impact of public decision-making on certainty for projects and on consequent business strategies will need to be carried out in the initial planning stages of many undertakings, and regularly thereafter, to anticipate risks of disruption and new opportunities that may emerge.

There are also a variety of legal frameworks that have not been established to address climate change but where the nature of the activities they control is connected to climate change. This indirect relevance will mean that governments, courts and interested parties may use these frameworks to drive behavioural changes related to climate change. For example, activities that are likely to cause harm to the environment absent appropriate safeguards are generally controlled by imposing a requirement for a permit, which in turn may impose conditions in order to maintain the permit and continue to carry out the permitted activities at a given facility. These may include certain emission limits or restrictions in operating times, and it may be that these conditions are made more restrictive in attempts to control industrial activities which contribute to climate change, or that enforcement patterns will change in response to public pressure.

Supply chains

Supply chains can represent a very substantial part of a company’s overall climate impact, but changes to supply chain behaviours may be beyond the company’s control. Addressing pressures to green supply chains and managing stakeholder expectations are therefore likely to be challenging endeavours.

The EU and the UK have indicated their intention to introduce demand-side policies aimed at requiring consumer-facing transparency in relation to climate change impacts in supply chains. There is also a trend towards greening products and supply chains through a combination of policies to incentivise greener but more expensive alternative production technologies. In addition, the EU Commission has touted the possibility of introducing personal liability for directors in supply chain diligence legislation, although this remains contested.

In the last few years, there has also been increased shareholder interest in Scope 3 emissions (emissions attributable to value chains) for larger emitters. Changing shareholder expectations may become a source of pressure for companies to take more active measures to manage the carbon intensity of their supply chains.

Route to market

As supply chains located in different parts of the world will reflect substantially different carbon intensities, global products businesses will likely be increasingly affected by carbon leakage mechanisms (such as the EU’s proposed Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, which aims to put a price on carbon for imports of certain goods from outside the EU in order to prevent companies from transferring production to countries that are less strict about emissions). They may also be affected by potentially restrictive import terms justified on the grounds of climate change policy. These will almost certainly discriminate against and between imported products, given that these footprints will differ between products that are otherwise comparable in trade law terms.

The EU’s latest proposals for the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism also contemplate sectoral agreements with third countries to simplify these adjustments where the country of origin already has a carbon pricing system, which may become another avenue for influencing the carbon pricing regimes and policies of countries outside the EU, in a similar vein to trade agreements.

A company’s route to market may be eased by government support. Historically, this has been the case in some power sectors, for example through take-or-pay offtake arrangements for power generating assets, or contracts for difference establishing floor prices for renewable power.

Consultation and advocacy with national policymakers, both by relevant industry associations and participants and by interested parties such as NGOs, may have important impacts for businesses whose global supply chains would be impacted by new restrictions on imports or carbon leakage adjustments.

Future emissions reductions

Companies may find themselves facing legal consequences for failure to achieve or plan for emissions reductions in a number of ways, not all of which are externally imposed. As already mentioned, companies could face legal action or other forms of stakeholder pressure to reduce their emissions or create more robust plans for future reductions based on commitments that the company has made voluntarily, or on the basis of a more general need to have adequate plans to secure the company’s performance in a low-carbon future.

There may also be consequences from regulatory changes as public authorities impose stricter conditions on emissions in order to meet their own targets and obligations in line with applicable duties. There may be legal challenges against companies and public authorities involved in developing projects that are in tension with emission reduction goals. In places where reduction targets have been imposed on specific sectors or the whole nation, whether as a matter of policy (as is the case in China and many European states) or as a matter of law (as in the UK), these targets may result in regulatory restrictions that require significant operational changes, and non-compliance may result in financial penalties or site closures.

Meet the team

Simon Duncombe Partner

London

Cat Greenwood-Smith Partner

London

Jonathan Isted Partner

London

Vanessa Jakovich Partner

London