International arbitration in 2021

The future of investor-State dispute settlement

Reform efforts continue amid ongoing legitimacy concerns

In recent years, some States have challenged the use of arbitration in investor-State disputes. They have sought to reaffirm their rights as well as limit their obligations vis-à-vis foreign investors by renegotiating their international investment agreements (IIAs).

In Europe, the European Union (EU) continues to push for the establishment of a multilateral investment court (MIC) that would replace the arbitration system, notably in the current discussions on the reform of the Energy Charter Treaty.

However, unlike in other recent bilateral investment agreements with third countries (eg Canada, Vietnam), the EU has failed to secure investment court systems (pending the establishment of the MIC) in its latest international investments treaties with the UK and China (the latter of which only contains a commitment to pursue negotiations on this point within the next two years).

As discussed in trend 4, the UK is expected to clarify its stance on investor-State dispute settlement (ISDS) in the new IIAs it is likely to conclude in 2021 to fill the gap created by Brexit. In the meantime, questions remain as to the protection of investors in investor-State disputes post-Brexit, given the lack of such provisions in the EU–UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement and the Japan–UK agreement, which do not provide for any ISDS mechanisms.

More globally, some States have continued their efforts to strengthen their rights in IIAs in a shift away from traditional investor-State arbitration. Only two IIAs (Hungary–Kyrgyzstan and Japan–Morocco) out of the 17 concluded in 2020 will directly provide for arbitration in investor-State disputes, while others merely include commitments to further negotiate in this respect.

The US–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA) – colloquially known as the ‘new NAFTA’ – entered into force on 1 July 2020. Pursuant to this trade agreement, the ISDS mechanism is only applicable to disputes between US investors in Mexico and Mexican investors in the US. Canadian investors in Mexico and the US (and vice versa) are no longer protected, with no ISDS between Canada and the US or between Canada and Mexico. Save in protected sectors (oil and gas, power generation, telecommunications, transportation and infrastructure), the substantive protections in the USMCA have been dramatically reduced in scope when compared with the NAFTA protections (no indirect expropriation or international minimum standard). Similarly, save in protected sectors, there are onerous preconditions prior to initiating arbitration (30 months before local courts).

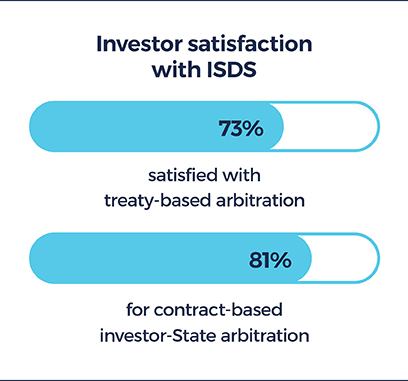

Despite the criticisms and these restrictions on ISDS in new instruments, the 2020 Queen Mary Survey on ISDS highlighted that investors are generally satisfied with the current arbitration system for ISDS even while investors identify areas for improvement, including a proposed code of conduct of arbitrators and consideration of mandatory mediation. Notably, investors are generally opposed to the creation of a MIC (56 per cent).

Recent reactions to the legitimacy challenges

In response to the challenges levelled against ISDS, reform efforts undertaken at the institutional level are also progressing:

- Following its work on the improvement of ISDS, in November 2020 Working Group III of the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) published for comment working papers on (i) an appellate mechanism (including the possibility to establish a permanent multilateral appellate body); and (ii) the selection and appointment of ISDS tribunal members (which refers to a Draft Code of Conduct for Adjudicators). The result of this consultation will be examined at the next session of Working Group III scheduled in February 2021.

- Working Group III and ICSID jointly developed the Draft Code of Conduct for Adjudicators. Apart from more traditional provisions on duties and responsibilities of adjudicators (including arbitrators) as well as disclosure obligations, the Draft Code also interestingly addresses ‘double-hatting’, ie adjudicators acting in different roles (counsel, arbitrator or expert) in several ISDS proceedings at the same time (by either enjoining adjudicators from double-hatting or, at least, disclosing it).

- The UNCITRAL Working Group II is also considering issues relating to expedited arbitration and the Secretariat is expected to prepare a revised draft of the expedited arbitration provisions in advance of Working Group II’s next meeting in March 2021.

- ICSID also continues its efforts to modernise its rules in order to increase transparency and efficiency in ISDS. In February 2020, ICSID published its Working Paper 4 setting out proposals for amendment of the ICSID rules, which focus, among other things, on disclosure of third-party funding.

The different initiatives undertaken by various stakeholders to address the perceived shortcomings of ISDS will continue in 2021 and could be crucial as ISDS proves more relevant than ever for investors subject to a heightened risk of arbitrary State measures.

Another tool that is gaining traction in this context is mediation. With the 2019 United Nations Convention on International Settlement Agreements (the Singapore Convention) creating an internationally enforceable framework for settlements reached by mediation, and ICSID launching new draft Mediation Rules, the groundwork has been laid for investor-State mediation to play a more significant role. The newest generation of IIAs has started to include express provision for mediation or conciliation, albeit largely on a voluntary basis. We expect to see more debate on whether mediation has a greater role to play in ISDS provisions in treaties in the year ahead.

Just as the Singapore Convention generated a wave of interest in mediation of commercial disputes, it is similarly contributing to renewed interest in alternative and creative methods for the resolution of investor-State disputes, whether through mediation, conciliation or other forms of engagement short of full-scale arbitration. It may be that more States seek to include mandatory pre-arbitration conciliation or mediation requirements in treaties – so far, though, that remains extremely rare.

COVID-19’s influence

As discussed in trend 6, measures and (announced) recovery plans adopted by States in response to the economic crisis may increase the risk of investor-State disputes in 2021. At the same time, if – and this remains the subject of heated debate – there is an avalanche of COVID-19-related claims, that is likely to exacerbate the existing legitimacy challenges to investment arbitration by stakeholders and the general public. Given the great impact of the pandemic on people’s daily lives and the sensitive nature of the measures, challenges by private investors could put ISDS back at the forefront of the public debate. In this respect, the Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment has notably called for an immediate moratorium on all arbitration claims by private investors against States and for a permanent restriction on all arbitration claims in sectors affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the existing tensions recently focused on rejecting traditional international arbitration and rebalancing States’ rights and obligations. Moving forward, investment structuring is bound to become even more crucial for investors who should seek to ensure that they benefit from effective ISDS protections.

International arbitration in 2021

- Introduction

- The future of remote hearings in a post-pandemic world

- COVID-19-related disputes: trends and predictions

- Insolvency and arbitration

- Arbitration in the EU and UK: a changing landscape

- The future of investor-State dispute settlement

- Investment arbitration trends

- Investment claims: project finance lenders have rights too

- Latest arbitral rules reforms

- Continuing economic woes for the construction and infrastructure sectors

- Arbitrators’ duties of disclosure in the spotlight

- Arbitration and climate change