Matei

Purice

Continental Europe Head of Global Projects Disputes, Paris

Major construction projects rely on complex supply chains that can span numerous jurisdictions on multiple continents, and supply chain disruption can have a significant, and often costly, impact on project execution. With increasing focus on supply chains from owners/operators and contractors alike, it is becoming an ever-more-prevalent cause of disputes in global projects, a trend we expect will only increase throughout 2023.

Key factors contributing to the global supply chain crisis

Since its outbreak, the COVID-19 pandemic severely disrupted the procurement and execution of construction projects, as well as their financial and supply chain sustainability. While the shock impact of the pandemic has largely, but not completely, abated, global events in 2022 further deepened the crisis in this sector. In particular, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and associated international sanctions, leading to rising global energy and commodity prices and soaring inflation, have had a marked impact on the sector. Coupled with cost pressures arising from global currency fluctuations, they have compounded an already challenging global supply chain situation.

‘With no immediate resolution in sight, we expect factors arising from the Russian invasion of Ukraine to continue to strain supply chains throughout 2023, leading to increased project execution risks and potential disputes.’

Tom Hutchison, Counsel

The increased scrutiny on supply chains in relation to disclosure and reporting requirements, particularly in relation to ESG, may also have an impact (at least in the short to medium term) as owners, contractors and suppliers take time to adjust to new compliance criteria being introduced in various forms globally. An example is the German Supply Chain Duty of Care Act, which obliges companies to comply with human rights and certain international environmental standards within their operations and supply chains (see our blog) – similar legislation has been proposed by the EU in the form of the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (see our blog). In addition, increased consumer demand for greener solutions will put pressure on supply chains as they transition to accommodate such demands.

What does supply chain disruption mean in practice?

Supply chain disruption has the potential to delay the progress of works and ultimately the completion of a project, eg because required materials or components are no longer available, the lead-in times are increased or delivery will take longer. It can also increase costs, as materials or components have to be sourced at a higher price than originally envisaged, or it may even be necessary to source an alternative, more expensive material or component for the project.

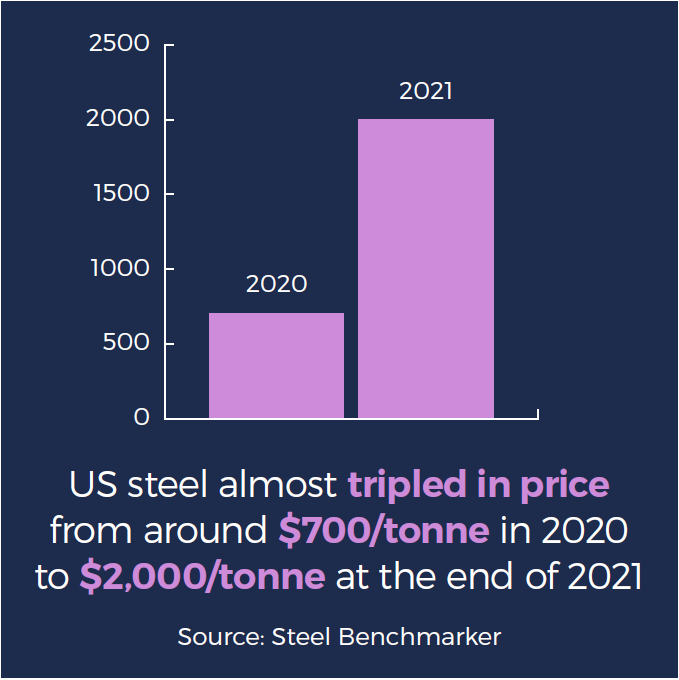

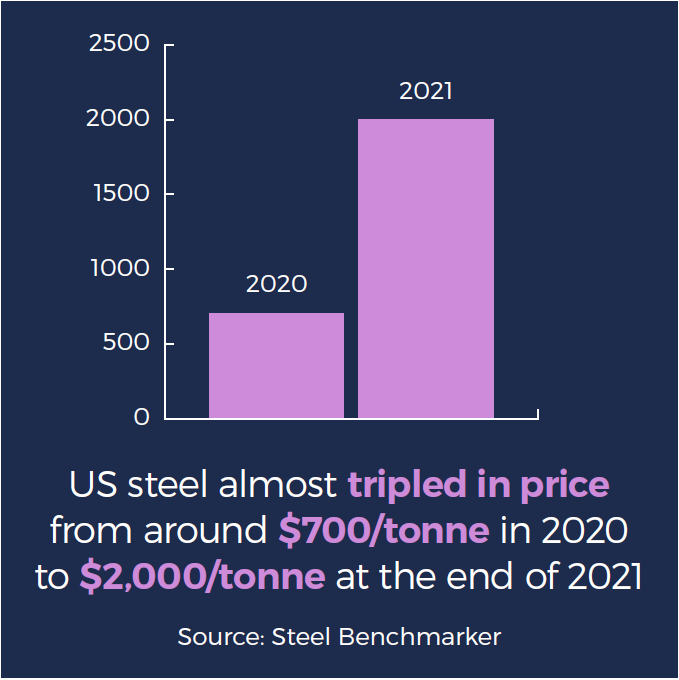

Steel, copper and timber are examples of building materials the supply of which has been disrupted in recent times. In relation to components, notable examples include turbines required for offshore wind projects and silica battery storage required for solar projects. The supply of specialist equipment, power, oil and other fuels and logistics can also be impacted. The price and availability of labour can also be affected by many of the factors that cause supply chain disruption.

The above pressures can also increase the risk of insolvency in the supply chain, with key suppliers and subcontractors potentially going under, a trend that we commented on in our 2021 Trends Report but which remains an equally great, if not greater, risk in the current climate.

Historically, contractors entering into fixed-price construction contracts were often able and willing to shoulder the risk of small increases in cost and/or minor delays caused by supply chain disruption – in effect, the risk would have already been priced in or built into the schedule. However, as became apparent during the COVID-19 pandemic, this is only commercially viable up to a certain point.

The impact on arbitration: an increase in claims

Given the severity of the ongoing supply chain disruption, we expect disputes to arise including in connection with the ability of contractors to claim schedule relief and/or reimbursement of additional costs under the terms of their contracts.

We anticipate increased reliance on (and disputes in relation to the operation of) provisions relating to the following.

- Price escalation: Historically such clauses have not been a point of real focus in construction contracts, but in light of the current economic realities, their use (and therefore the need to include them in contracts) is once again key (read our blog post to find out more).

- Currency fluctuation: Such clauses can be helpful where the cost of materials and labour is in a different currency to the contract price.

- Variations: An employer might seek to mitigate the effects of disruption by varying contractual terms, eg amending the specification to permit the use of a different component.

- Nominated supplier: A clause requiring the contractor to use a specified supplier (or to select from a limited number of specified suppliers) can impact the contractor’s ability to mitigate the impact of supply chain disruption.

‘We have seen increased focus in the past year on the inclusion and operation of price escalation, currency fluctuation and nominated subcontractors/supplier provisions – a trend that we expect to see continue in 2023.’

Matei Purice, Continental Europe Head of Global Projects Disputes, Paris

Legal concepts such as frustration, force majeure, imprevision or change in circumstances may also gain more attention in an effort to avoid the consequences of delayed (or lack of) performance arising from disrupted supply chains. Change in law clauses are also likely to be tested in light of both sanctions and ESG obligations (including relating to supply chain monitoring and climate change) where there is a material impact on the ability to use particular or chosen suppliers. That said, we expect their successful use to remain limited to specific exceptional cases.

Looking forward: potential solutions to limiting the risks generated by supply chain disruption

Practical steps that parties can take to reduce the impact of global supply chain disruption include the following.

- Reshore, near shore or diversify the supply base. An example is the ‘China plus one’ strategy, ie establishing an additional supplier outside China. Onshoring requirements are frequently imposed on State-backed energy transition projects, to ensure domestic economic benefits.

- Make use of new technology, for example digital supply networks (DSNs), which provide live data on the availability and movement of materials. These can alert parties to potential problems in the supply chain at an early stage, therefore buying more time to respond.

- Consider alternative contracting structures. Project stakeholders should consider adopting alternative structures such as partnering and alliancing contracts that may help balance some of the risks arising from the global supply chain crisis (see our blog).

‘Ensuring resiliency of supply chains will continue to be a business imperative for the foreseeable future. Parties will need to be thoughtful about addressing various pressures from inflation to insolvency and preparing for further geopolitical instability. The recent continual crisis context will be shaping disputes for years to come.’

Erin Miller Rankin, Partner